By Samantha Latson

The group—men, women and children—followed Father Michael L. Pfleger’s lead. They kneel and place their palms where blood had been shed. “Peace, peace, peace,” the crowd of dozens shout in unison, commanding the streets and all within earshot to yield to their prayer for change.

Months later, with summer well ended and the first snow of winter already fallen, the marcher’s voices and chants still fill my head. Their hope. Their journey through some of Chicago’s deadliest streets in their fight to turn the cycle of violence around. I still see them, hear them clearly. And I doubt that I will ever forget.

____________________

____________________

"I learned that beyond the stereotypical stories that plague Black communities there are vibrant complex stories of daily life."

____________________

____________________

|

| Father Michael L. Pfleger leads Peace Marchers in prayer at corner where two people were shot. |

Weeks earlier, Pfleger announced a call to action, exclaiming, “We’ve saved the whales, we’ve saved the birds, but our children are becoming extinct. We must save our children!” His plan with the Faith Community of St. Sabina: To “invade” the city in an effort to save our children.

As a reporter, I decided to be there to chronicle for the entire summer each march with my professor. It was my own self-made internship, as my pickings for a summer job at a newspaper were slim to nonexistent due to the pandemic, though my need for real-life reporting and writing experience remained necessary to building a career in journalism.

My assignment was simple. Cover the marches on Fridays: take notes, take pictures—lots of them, plus video. Observe and be prepared to do a lot of walking.

I remember covering the weekly marches, sometimes running with my camera, trying to capture Pfleger as he prayed, hugged, and encouraged people, often strangers, he encountered in the streets.

At other times, I stood amid the crowd—the young and the old—capturing them and the scene—the motorists who honked in support as the human caravan flowed through the streets, or a person having emerged from a storefront and crying or applauding the church’s efforts. Or I walked alongside the marchers, even as the last glimpse of sun faded on a summer city night with them still calling on the Lord for divine intervention.

I’ll never forget the marchers who oozed with excitement as the green truck, which led them, outfitted with loud speakers, turned every corner, blasting Civil Rights anthems and other songs of Black pride and empowerment. Marvin Gaye’s “Inner City Blues,” Bob Marley’s “Get up Stand up,” and Public Enemies “Fight the Power” rang throughout the course through the city’s South Side.

Lyrics of hope permeated the streets, the handheld signs of some of the marchers—and also some fists—raised in solidarity.

“The world won't get no better, if we just let it be, the world won't get no better, we gotta change it, yeah, just you and me,” Teddy Pendergrass’ voice blared as Harold Melvin & The Bluenotes, “Wake Up Everybody” played. “So I'm gonna stand up, take my people with me, together we are going to a brand new home.”

|

| Reporter Samantha Latsson reporting on the scene at the Summer Peace March in 2021. |

There were few, if any, new homes along the prayers’ route. Wrought-iron fences, darkened storefront churches sealed by metal bars and locks. Evidence all around that there is likely more hurt than hope for so many here and the offer of prayer a perhaps welcome balm.

That seemed the case one Friday evening for one woman who the prayer warriors happened upon with “Fight the Power,” blaring and a man apparently forcing her out of a sedan with a baby in the summer heat, abandoning them on 76th Street.

The woman screamed, but the driver seemed unfazed, speeding away in the wind. Pfleger and his followers stopped. They prayed for her as the young woman cradled the child in her arms. The pastor’s right hand rested gently on the back of her head, as he spoke a word of life into her ears, and afterwards others in the church sought to offer help and services.

That is what I remember.

I don’t know all that I was expecting from my summer assignment—maybe a few clips and experience doing up close and personal, real-life journalism about a critical subject in a big city that deserves much more news media attention. But I got so much more. I learned the importance as a journalist in simply being there. Of sticking around and returning to the scene long after the news cameras have packed up and gone.

I learned that beyond the stereotypical stories that plague Black communities there are vibrant complex stories of daily life. Of people working to effect change. I learned that my lens and my pen as a journalist can make a difference. I learned that the stories journalists encounter—the faces, voices, lives and people’s journeys, even if tumultuous and filled with tears—can become the tapestry of experiences that make you, even as a reporter, better for having taken that journey with them.

I can’t forget.

Even now as a graduate student, many miles away at Indiana University, I miss those summer nights, bearing witness to the “good news” Father Pfleger and St. Sabina extend to the community beyond the church’s walls. The light that beamed bright amid the darkness—natural and spiritual—as families came out of their homes, smiling and waving from their porches at the passing prayer caravan. The young Black men who stood on the sidewalk, giving the white Catholic priest a hug, talking to him like he was one of the guys, showing respect.

Summer has long since ended and another looms. Cook County has recorded more than 1,000 homicides, with a reported 797 in Chicago alone, according to city officials. And although I am far from home, I am continuously made aware of the violence still plaguing Chicago’s streets. I awaken to headlines of yet another child being gunned down.

It reminds me why Chicago needs Father Pfleger and St. Sabina, and the entire faith community of Chicago. I witnessed the peace, the tears, the hope and the help one summer as people of faith invaded the streets. Their impact might not show up as empirical data. But how do you measure the power or effect of faith and prayer?

I don’t know.

But I cannot shake from my mind the image of people kneeling on one accord, palms stretched on the ground, and voices declaring, “peace, peace, peace,” invading darkness where blood was shed.

Email: Samanthalatson22@gmail.com

|

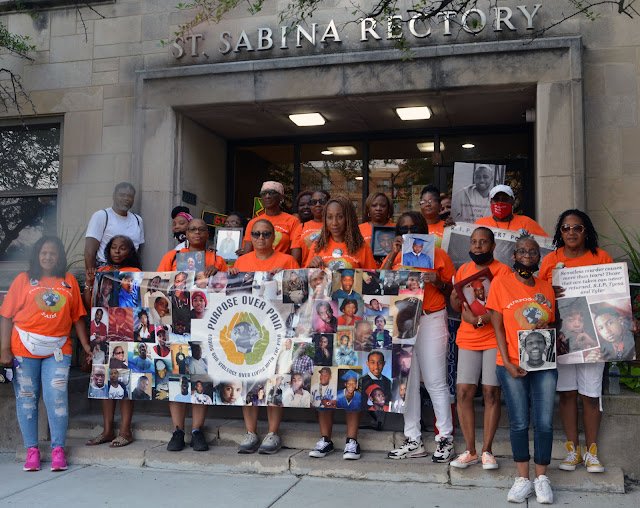

| Mothers of murdered sons and daughters were instrumental in the summer marches as members of Purpose Over Pain, a group based at the Faith Community of St. Sabina |